The Effects of Wind Turbines on the Environment

I. Wind Turbine Regulations in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania does not have statewide siting regulations for industrial wind projects. Local governments regulate some of the siting concerns. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) regulates the project as if it were a road construction project. Its permitting process stops at the base of the tower. Impacts to rare plants, wildlife, and watersheds, are handled by DEP.

If you are reading this because there’s talk of a wind project coming to your township, contact SOAR. We are here to help you understand the permitting process and how you can work with local officials to protect your community.

Don’t be complacent if you find out your township already has a wind ordinance. A careful read often reveals that they don’t offer much protection to wildlife, watersheds, or nearby communities.

A. Local Control in Pennsylvania

In Pennsylvania, the negative impacts of wind turbines on human health are regulated by the local municipality, since it has the police power to regulate land use. One of the key regulations is setbacks – the required distance between a structure and a property line.

Since wind turbines are structures, there should be wind regulations in every municipality that stipulate the setback distance from a wind turbine to a property line. Unfortunately, this setback distance is often inadequate and may fail to protect residents from noise, infrasound, shadow flicker, ice throw, or wind turbine failures.

The enabling statute that gives municipalities the police power to regulate the use of land is the Pennsylvania Municipalities Planning Code (MPC). The MPC was enacted in 1968 and authorizes municipalities across Pennsylvania to adopt zoning ordinances for the purposes set forth in the MPC.

Most Pennsylvania townships have their own zoning, and some choose to operate under county zoning regulations. Rural, less developed, and less populated areas in Pennsylvania are less likely to have zoning. For those townships without zoning, comprehensive plans can guide development and an ordinance can regulate impacts. A good resource for examples of land use ordinances, zoning, and other regulations is the Pennsylvania Land Trust Association’s Library.

A municipality’s Subdivision and Land Development Ordinance can regulate development on steep slopes, turbine height, setbacks, noise limits, etc.

Zoned or not, municipalities have the police power – and the responsibility - to protect the public health, safety, morals, and general welfare of the citizens.

It’s important to have regulations in place BEFORE the project application is submitted since any new ordinances enacted AFTER the application do not apply. However, municipalities can call for a Curative Amendment, which will give them time to correct an inaccurate regulation.

Pennsylvania Constitution: The Environmental Rights Amendment

On May 18, 1971, Pennsylvania’s voters ratified, by a four-to-one margin, what is now Article I, Section 27 of our state constitution–the Environmental Rights Amendment:

The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment. Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come. As trustee of these resources, the Commonwealth shall conserve and maintain them for the benefit of all the people.

Although the amendment has existed since 1971, it was not often put to the test. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court, however, used Article I Section 27 to strike down part of Pennsylvania’s Act 13. The Act took some permitting powers away from local governments and gave them to the state. A 2017 article explains what happened here.

1. Local Control: Industrial Wind Projects and Zoning

If your municipality has zoning, wind developers apply for a Special Exemption or a Conditional Use permit. The Zoning Hearing Board reviews a Special Exception application, while the Supervisors review a Conditional Use application. A developer may also apply for a Variance, but must prove the current regulations inflict “unnecessary hardship” on the applicant.

A recent Pennsylvania Supreme Court Ruling has endorsed the relevancy of testimony and evidence submitted by objectors from other municipalities. Since industrial wind turbines are huge structures, their impact is not limited to municipal lines, making it more likely that neighboring objectors will be heard from outside the municipality where the project is located.

A developer can file a curative amendment to challenge a municipality’s zoning ordinance.

More information can be found here.

More municipalities and counties are adding a Wind Overlay Zone to their zoning maps to show where industrial wind projects can be built. In 2009, a manual for townships was funded by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania that used Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Data for wind energy planning.

The study suggested that ecological concerns could be factored into these overlay maps if Natural Heritage Data were used. Only Blair County in Pennsylvania had used an overlay map for wind development when this manual was published, but since then more townships have adopted this designation. Pages 13 and 14 list the townships where wind development would conflict with Natural Heritage conservation areas. Sadly, since this manual was published, some of these sensitive ecological areas now host industrial wind turbine projects. The Big Level Wind Project in Hector Township is just one example. Photos and more details about Big Level Wind Project are found at this blog.

2. Local Control: Industrial Wind Projects and No Zoning

A municipality’s Subdivision and Land Development Ordinance, or a stand-alone wind ordinance, can regulate development on steep slopes, turbine height, setbacks, noise limits, etc. If a wind project is planned for a rural township, that township is most likely regulated by the Second Class Code Township Code.

Township Supervisors are charged with ensuring the “health, safety and welfare of the citizens of the township” and Section 1506 states: “General Powers.--The board of supervisors may make and adopt any ordinances, bylaws, rules and regulations not inconsistent with or restrained by the Constitution and laws of this Commonwealth necessary for the proper management, care and control of the township and its finances and the maintenance of peace, good government, health and welfare of the township and its citizens, trade, commerce and manufacturers.”

Section 1516 states: “Land Use Regulations. --The board of supervisors may plan for the development of the township through zoning, subdivision and land development regulations under the act of July 31, 1968 (P.L.805, No.247), known as the "Pennsylvania Municipalities Planning Code.”

Section 1527. “Public Safety. --The board of supervisors may adopt ordinances to secure the safety of persons or property within the township and to define disturbing the peace within the limits of the township.”

Township Supervisors in Pennsylvania may not enact an ordinance that would be so restrictive that a legitimate business would be excluded from development in the township, but setbacks, height limits, and noise restrictions are often included in wind ordinances.

3. A Sampling of Pennsylvania Wind Ordinances

A model wind ordinance was drafted for Pennsylvania in 2006 by developers and officials with the purpose of “protecting the public health, safety, and welfare.”

Setbacks, noise, and height restrictions in the model ordinance are compared to more recent ordinances, to show that townships are now enacting more protective restrictions since the model ordinance is out of date and woefully inadequate. After each example is a number that corresponds to the ordinances listed below.

Setbacks:

Setback is 1.1 times the turbine height, or a distance of not less than the normal

setback requirements for that zoning district to the property line. (1)

Setback is total height plus 200 feet to property line. (2)

Minimum setback to property line is 1,500 feet. (3)

Setback is 3,000 feet to property line. (4)

Setback is 2,500 feet to property line with an occupied building. (5)

Setback is four times the maximum height to the residential lot; minimum is 1,500 feet. (6) and (7)

Noise:

A good explanation of Wind Turbine Noise is found here.

Note: dBA represents human hearing and is the weighting system used for all community sound measurements. dBC is used to evaluate low frequency sounds (under 60 Hz).

The Lmax standard means the limit cannot exceed a specified level while the Leq standard means the noise limit is an average. The wind industry prefers to use Leq, but Lmax provides better protection to the community.

Shall not exceed 55 dBA as measured at the exterior of any occupied building on a non- participating landowner’s property. (1)

Shall not exceed 50 dBA at property line. (2)

Noise shall not exceed 55 dBA at the site’s property line. (3)

Not more than 45dB within a reasonable margin of error as measured from the property line. (4)

Audible sound shall not exceed 55 dBA as measured at the exterior of any occupied building on any adjoining property line. (5)

Shall not exceed 45 A-weighted decibels, and shall not exceed 45 C-weighted decibels to lot line. Uses Lmax standard, and not based on average. (6) and (7)

Shall not exceed 55 dBA as measured at the exterior of any occupied dwelling on another lot. Maximum noise level using a Lmax standard, and not based on an average. (8)

Height: Total height includes the the tower height and the highest point of the vertical blade

Maximum total height: no restriction. (1)

Maximum total height of 450 feet. (2)

Maximum total height of 350 feet. (3), (6) and (7)

No height restriction, but turbines are limited to 2 MW. (4)

The hub height shall not exceed 335 feet. (5)

Maximum total height of 400 feet. (8)

Property Values: Only included in (6) and (7)

A property value analysis requires a qualified appraiser who determines the actual impacts upon residential property values of a similar set of wind turbines in a mostly rural community within the United States. More on this topic in Section VII.

Shadow Flicker or Wind Turbine Flicker:

Shadow flicker occurs when the sun is shining directly behind a wind turbine and the turning blades cast moving or flickering shadows on nearby residences or public use areas. This occurs only during low sun angles and usually only a few hours per year, but it can present an annoyance to nearby residents.

All of the reviewed Pennsylvania ordinances allow shadow flicker, but other areas of the country may restrict shadow flicker to 0 hours at the property line. There is new technology (Vestas Shadow Detection System) that is able to eliminate shadow flicker on non-participating properties and this eliminates the municipality from having to enforce a shadow flicker time limit. See Mason County, MI experience with VSDS and restricting shadow flicker to 0 hours. Another control system is described here.

II. Wind Turbine Regulations Outside of Pennsylvania

Some states regulate the siting of wind projects, while others use a combination of local and state regulations. A good summary of what other states require is found here.

III. Wind Turbine Noise

Lisa Linowes, the Wind Action Group Executive Director, has written a well-researched article on wind power and health effects.

The 2014 Health Canada study is often cited by wind proponents. Acoustician Stephen Ambrose wrote a rebuttal to the study. Read here. The Canadian Medical Association Journal published another rebuttal analysis by Carmen Krogh and Robert McMurtry.

Dr. Robert McCunney is often hired by wind companies as an expert witness to testify that a proposed wind project will not impair human health, yet he has never treated anyone complaining of turbine-related symptoms or conducted any original field research, rather he relies on literature reviews. Read more here.

In 2011, during a Public Service Board Hearing in Vermont, “Attorney Margolis produced the transcript of a 2010 webinar on wind turbine noise and health that McCunney had participated in. In it, McCunney said that for a wind turbine near his home, he would want to have noise levels ‘below 35 decibels…maybe 40.’ A 45-decibel sound is perceived as twice as loud as 35 decibels.”

- The World Health Organization (WHO) released new guidelines on wind turbine noise in 2018. WHO uses the noise measurement of 45 dBA Lden (45 A-weighted decibels, day-evening-night level), which is the maximum noise limit at any permanent or seasonal no-participant residence regardless of time of day.

Sherri Lange, CEO NA-PAW, Exec. Director Canada, Great Lakes Wind Truth and VP Canada Save the Eagles International, wrote an extensive article regarding these long-awaited guidelines

E. Sound from industrial wind turbines is complex.

- Most of the wind projects in Pennsylvania are on higher elevations than nearby communities, which are usually established in the valleys. When wind turbines are sited on higher elevations, the sound waves may be amplified by mountains containing ravines. The ravines act like a bullhorn, making the sound louder and able to carry farther.

- Home construction materials may reduce noise, but wind turbine noise, at lower wind and blade speeds, contains more low frequency sound. Lightweight building structures may not attenuate lower frequency noise as well as higher frequency noise.

- Dense materials like brick or stone walls do a better job of blocking low frequencies, but doors and windows permit the low frequencies to enter the home.

- Sounds from wind turbines that travel to the same destination are louder than the individual sounds added together. Background sounds, such as leaves rustling, add even more sound.

- Rural areas usually have low ambient noise levels, so adding sounds from wind turbines may be very annoying – especially at night when ambient noise levels drop and wind turbine noise may be higher. Wind turbine blades may produce thumping sounds as the blades pass the tower. This sound may waken people at night or cause annoyance.

- A worst-case scenario may occur at night when cool air is trapped at the ground level and winds are calm, but the winds are blowing more strongly at blade level where it is warmer. The thumping noise is then trapped in the low-lying areas. Sounds may be more than twice as loud as expected. Since most sound measurements are taken during the day, prediction models fail to account for the nighttime noise.

- One type of sound, called amplitude modulation, occurs when whooshing/thumping sounds are produced by wind turbines. Some residents describe them as “jet engines or washing machines in the sky.”

IV. Wind Turbines Produce Infrasound

- Infrasound is sound waves with frequencies below the level of human hearing. Humans can feel infrasound, but not hear it. Elephants use infrasound to communicate.

- Many spinning structures produce infrasound: the ocean waves hitting the beach, tornadoes, and window fans. The larger the producer, the more infrasound is produced. Larger turbines tend to emit more infrasound and more low frequency sounds than smaller turbines.

- Keith Stelling, MA, (McMaster) MNIMH, MCPP (England), compiled an extensive report in 2015 on Infrasound for the Waubra Foundation: Infrasound, Low Frequency Noise and Industrial Wind Turbines.

Similarly, there is medical research…which demonstrates that pulsating infrasound can be a direct cause of sleep disturbance. In clinical medicine, chronic sleep interruption and deprivation is acknowledged as a trigger of serious health problems.

- A good summary of wind turbine infrasound issues by Sherri Lange is written here.

- Why do some people become ill from infrasound, while others are unaffected? Some people are more sensitive to the sound waves, just as some people get car sick and others don’t. Medical researcher Alec Salt, PhD. has been researching the effects of infrasound on the human ear. Resource documents by Dr. Salt are listed here.

- An extensive series of articles written by Rick James and Jerry Punch include Dr. Salt’s research and provide an excellent explanation of infrasound and why wind turbines are a health risk.

V. Noise Experts

Both Rick James and Robert Rand are qualified as expert witnesses and are highly recommended for advisory and review work.

Rick James

E-Coustic Solutions, LLC

Okemos, MI 48805

Tel: (517) 507-5067

Email: rickjames@e-coustic.com

Acoustical Consulting and Expert Witness Services related to:

- Computer Prediction and Modeling of Noise

- Sound Measurement Review (Infra through 20kHz)

- Noise Control and Mitigation Options

- Community Noise from Audible, Infra and Very Low Frequency Sound

Effects of Noise on People and Communities

Brief Bio:

Richard James, E-Coustic Solutions, LLC (E-CS) of Okemos, MI, has over 50 years of experience in acoustics working as a consultant to major industrial companies. He joined the Institute of Noise Control Engineering (INCE) in 1973 and was a Member until 2017. He has been actively investigating wind turbine noise since 2006 when reports of adverse health effects were first heard from people living near 1.5 MW wind turbines. Since that time Mr. James has conducted studies of many industrial scale wind projects, published several papers, including several in peer reviewed/professional journals, and participated as an expert witness or an advisor to attorneys in many hearings and court cases. Mr. James has been qualified as an expert witness with expertise in the measurement of wind turbine sound and its impact on humans in US, Canadian, and New Zealand courts. In a Michigan Circuit Court, Mr. James was deemed an “acoustician with expertise in measurement of wind turbine noise and its effects on people” and an acoustician qualified to opine that a plaintiff’s symptoms were caused by the defendant’s wind turbines under the Daubert Hearing process.

Robert W. Rand, ASA, INCE (Member Emeritus)

Rand Acoustics, LLC

65 Mere Point Road

Brunswick, ME 04011

Tel: 207-632-1215

Web: http://randacoustics.com

"Mr. Rand is owner of Rand Acoustics, LLC, a Member Emeritus of the Institute of Noise Control Engineers (INCE) and a Member of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) with over forty years of experience providing environmental and technical consulting services to power generation, military, medical, commercial, industrial, and community projects.

Mr. Rand's experience in general acoustics includes industrial noise control, environmental impact assessment, interior acoustics, and electro-acoustics, with ten years in the Noise Control Group at Stone & Webster Engineering Corporation, and five years of consulting projects for DARPA and the U.S. Army. He has conducted environmental acoustic analyses, project engineering and budget management, permitting reviews, acoustic testing, noise control design and costing, and operations monitoring activities for power generation and commercial projects. Rand Acoustics was founded in 1996 as an independent consulting firm."

A few examples of Robert Rand’s work:

Robert Rand’s work on infrasound produced by turbines in Falmouth, Massachusetts

is important: adverse health effects were even experienced by the researchers. Another report on Falmouth turbines is here.

Robert Rand critiqued a noise impact report prepared for NextEra’s Golden West Wind Energy Center in El Paso County, Colorado and found it contained several errors.

VI. Wind Turbine Setbacks

A. The American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) offers a good definition of setback:

“A setback for wind turbines defines the minimum distance a turbine can be built from residential structures, property lines, roads, environmentally or historically sensitive areas, and other locations. Setbacks can be set by federal, state, and/or local governments depending on the project specifications. Setbacks can be a fixed distance or a distance relative to the turbine height (e.g., 1.2 times the turbine tip height).”

AWEA also explains that, “Setbacks help protect public safety, and no member of the public has ever been injured by a turbine.” That’s certainly good news, but is it true?

Perhaps so, but injury could also refer to negative health impacts caused by wind turbines. If that’s so, then wind turbines have injured a lot of people because they’ve been sited too close to homes.

As wind turbines get taller, setbacks get longer. When the wind industry helped to draft the Pennsylvania wind model ordinance in 2006, they convinced officials that a setback to the property line of 1.1 times the turbine height was sufficient, stating it’s the “industry standard.” It’s like the number was derived from thin air; no scientific evidence was given as to why 1.1 times the turbine height is safe.

Fortunately, that industry standard is no longer accepted by municipalities, since wind turbine noise has affected the health of thousands of people living too close to wind turbines. Additionally, we now know that wind turbines can throw big chunks of ice or throw large blade fragments a considerable distance.

But how far should wind turbines be sited from property line? As explained earlier, sounds from wind turbines are complex and vary with terrain, time of year, and weather. Different models of turbines have different sound ratings, too. It’s also difficult to actually measure sound.

B. Setbacks for Safety

Three scientists actually used science to determine a safe setback for wind turbines from the property line. Here’s an abstract of their research:

“Setback distances established by regulatory authorities to minimize the probability of blade fragment impact with roads, structures and infrastructure can often have a significant impact on wind farm development. However, these minimum distance requirements typically rely on arbitrary rules of thumb and are not based on a physical or probabilistic analysis of blade throw. The work reported here uses a probabilistic approach to evaluate the effectiveness of current standards and to propose a new technique for determining setback distances. This is accomplished through the use of a dynamic model of wind turbine blade failure coupled with Monte Carlo simulation techniques applied to three different wind turbines. It is first shown that common setback standards based on turbine height and blade radius provide inconsistent and inadequate protection against blade throw. Then, using a simplified dynamic analysis of a thrown blade fragment, it is shown that the release velocity of the blade fragment is the critical factor in determining the maximum distance fragments are likely to travel. The importance of release velocity is further verified through simulation results. Finally, a new method for developing setback standards is proposed based on an acceptable level of risk. Given specific wind turbine operational parameters and a set of failure probabilities, the new method leverages realistic blade throw modeling to produce setback standards with a valid physical foundation.”

Three turbines, surprising results

The engineers selected three different sized turbines for their study, a 660 KW, a 1.5 MW and a 3.0 MW. Blade radius for each respectively was: 77 feet, 115 feet and 148 feet with hub heights of 164 feet, 262 feet and 262 feet.

The wind turbines with lower power output have smaller rotors that rotate at higher speeds and that’s an important point because the engineers found higher velocity leads to longer blade fragment throws in the event of blade failure. The setback formulas used in local ordinances which are some multiple of hub height and rotor diameter fail to take this into account and come up with setbacks far short of where blade fragments can fall.

As an example, the throw distances calculated for these three turbines were: 1440 feet for the 660 KW turbine, 1935 feet for the 1.5 MW turbine and 1726 feet for the 3.0 MW turbine. The shorter 1.5 MW turbine threw fragments even further than the larger 3.0 MW model, over 200 feet further!

The full research article explains exactly how to calculate throw distances based on the operational specifications of specific wind turbine models. In all cases in the article, even with the smallest 660 KW turbine, the throw distance was far greater than the 1.2 times the turbine height.

C. Setbacks for Noise

Unfortunately, sufficient noise setbacks are difficult to determine until wind turbines are built and functioning. Consequently, the industry uses sound modeling to determine a noise impact study. Since the municipal wind ordinance needs to be developed before any wind project applications are submitted, this best-case scenario is not feasible.

- Rick James has written about his concerns regarding a setback for noise.

“I would argue for a consensus on a minimum setback of 2km, not because it is safe for all, but because it is more easily supported in a public forum as being reasonable. 2km does not appear to be a “0” tolerance position. 5km or 10km does. We do not regulate other pollutants to a “0” risk level because it becomes too hard to justify the broad impact of such limits.” - The Lancaster County Nebraska working group produced a fact sheet about Industrial Wind Turbine Noise that lists a number of noise studies and setbacks. Setbacks ranged from almost 8,000 feet in Catarunck, Maine to Allegany, New York, which has a 2,500-foot setback. The working group recommended:

“The appropriate setback distance must be measured from the non-participant’s property line, not their residence. To ensure citizen health, safety, and property rights, the setback should correspond to a distance of ten rotor heights, or not less than one mile from the non-participant’s nearest property line, (unless agreed to).”

The one-mile setback was actually approved by the Lancaster County (NE) Board in February 2019 and it stuck for just one month. In March 2019, the County Board amended the setback to “five times the wind turbine's height to a nonparticipating property owner's home or two times the height to the property line, whichever is longer. For a 500-foot-tall wind turbine, that would be 2,500 feet, which is just less than half a mile.”

Why the change? Most likely because NextEra Energy Resources wants to build a wind project in the southern part of the county. - Unfortunately, since Pennsylvania’s ridges are the only areas where wind development can even be considered, developers don’t have the capacity to move wind turbines far enough away to protect communities. Consequently, many wind ordinances in Pennsylvania have insufficient setbacks.

- Research shows that sound travels differently over flat land compared to hilly areas with ridges and valleys. This means that some of the Sound Modeling Software that predicts noise from wind turbines is inaccurate, if it uses flat terrain as a prediction of noise levels.

A peer-reviewed paper was published by The Royal Society of London in 2017 that involves research on the sound propagation from a wind turbine in hilly terrain. The author states,

“Sound propagation outdoors can be strongly affected by ground topography. The existence of hills and valleys between a source and receiver can lead to the shielding or focusing of sound waves. Such effects can result in significant variations in received sound levels. In addition, wind speed and air temperature gradients in the atmospheric boundary layer also play an important role. All of the foregoing factors can become especially important for the case of wind turbines located on a ridge overlooking a valley.”

In Conclusion:

Rick James explains in a letter to SOAR in 2017:

If one wanted to have the simplest standard for setbacks, use what was put into the law in Poland: Limit wind turbines to setbacks of at least 10 times the total height from the base of the tower to the tip when it is at the top. For the new, larger towers and longer blades that are about 600 feet this puts the setback at 6,000 feet. Smaller WT, like the 1.5 MW wind turbines installed in the late 2000s and early 2010s would have setbacks of about 4,500 feet. If the setbacks are to property lines, this rule will accomplish the same degree of protection as the 35 dBA/50dBC not-to-exceed limits and require no sound measurements for enforcement.

Could these setbacks be considered a taking of property rights? Mr. James explains:

“The 35 dBA has withstood legal challenges in Oregon and other jurisdictions in the U. S. and other countries. The reason it is not exclusionary is because the developer can always ask non-participants to sign an agreement where they agree to allow noise to trespass onto their property after given full disclosure of the risks of doing so. Thus, the non-participating landowner becomes a participant and the setbacks move to the next property away from the project. It is the industry’s efforts to claim use of other’s properties that is a taking.”

When a township grants a permit to a developer that gives them rights to use of properties against the will of the proper landowners, without consent and compensation, they are allowing trespass to occur.

A landowner’s right to use their property, as they wish, stops at their property line. Beyond that, one person’s acceptable use becomes the neighbor’s noise complaint. No industry is allowed to create a public nuisance or cause adverse impacts on others without their consent and compensation. That is a major feature of our Constitution, which prohibits even the government from using our property without exercising eminent domain.

The township supervisors should be worried about creating illegal takings from township residents. All the industry needs to do is to be willing to pay the costs of annoying the neighbors and for those neighbors to accept liability for any health or other damages based on full disclosure of the risks. This is a common way to handle these situations.”

VII. Wind Turbine Projects and Property Values

Do Wind Turbine Projects Reduce Property Values?

The short answer is, "YES," but keep reading if you'd like to know more.

VIII. Wind Turbines and Visual Impacts

Yes, there is visual (aesthetic) damage when wind turbines are placed close to homes. A study in England and Wales supports this.

Closer to home, landowners in Texas, neighbors of the Horse Hollow Farm, claimed that “negative aesthetic impacts of a wind project by a neighboring landowner constituted a nuisance.” Although the court recognized the wind farm’s impact on the view and the emotional reaction this could cause, it did not rule it to be a nuisance.

Here is a useful report, “A Visual Impact Assessment Process For Wind Energy Projects,” published by the CleanEnergy States Alliance, that pertains to public lands. “The purpose of this guide is to facilitate the adoption and use of effective state and local policies, practices, and methodologies to evaluate the visual impacts associated with wind development projects.”

Developers take steps to minimize the visual impact of a wind farm by:

In addition, the visibility of a wind farm is influenced by factors such as:

The visual impact of a wind farm is assessed on a case by case basis through the resource management consent process.

Pennsylvania concerns:

In Pennsylvania, wind turbines are built on mountains, so some of the above visual mitigation steps just aren’t feasible. However, more municipalities are requiring that wind developers conduct a Visual Impact Assessment so residents can see how the turbines will impact the viewshed.

The Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office (PA SHPO) has issued guidelines for projects with potential visual effects on historic buildings, structures, and landscapes. It states that the Section 106 and the State History Code authorizes the office to provide comments on the effects a project (federally funded) may have on historic properties. The document outlines the process in order to identify the historic resources whose integrity might be diminished, which could affect a property’s National Register eligibility.

The guidelines state that the initial Area of Potential Effect (APE) for wind turbines will be 5 miles. Projects subject to Section 106 of the NHPA review require execution of a Memorandum of Agreement by the Federal agency, PA SHPO, the project applicant, and any consulting parties in order to address the adverse effect of the project.

Preservation Pennsylvania, a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving Pennsylvania’s historic resources, featured the potential impact of wind turbines on the Dutch Corner Rural Historic District and SOAR’s efforts to stop the wind project in pages 4 and 5 of its Jan-March 2011 newsletter. Since that article was written, Dutch Corner has been listed in the National Register and the proposed wind project was terminated. Unfortunately, a new wind company is now proposing the CPC Kettle Wind project above Dutch Corner. SOAR’s efforts to stop it continue – see more in the Chapters section, Friends of Bedford County Mountains.

Even though wind projects usually receive federal funding through the Production Tax Credits (PTC), or Investment Tax Credits (ITC), the wind projects are not considered to be federally funded projects, so Section 106 of the NHPA review does not apply.

Wind developers do acknowledge that industrial wind turbines on Pennsylvania mountains are hard to hide. Some people think the turbines are beautiful, others think they are eyesores. Broad Mountain Power, at the bequest of the Zoning Hearing Board, conducted a visual impact study for its proposed project on Broad Mountain in Packer Township, Carbon County, PA.

Here’s what is posted on their website:

“What will the visual impacts be from the Project?

Broad Mountain Power acknowledges public comments and concerns related to potential visual impacts. To show anticipated visual changes associated with the Project, high-resolution photographs were taken from 15 vantage/viewpoints surrounding the Project and computer-enhanced image processing was used to create realistic photographic simulations of the proposed wind turbines. The computer-generated photo-simulations were filed as part of the zoning application package for Packer Township.”

Conclusion:

The bottom line is that tall wind turbines on tall mountains change the viewshed. People who support wind development in Pennsylvania don’t mind it, people who don’t want the turbines in their community don’t want to see their beautiful mountains marred by wind turbines. Unfortunately, the courts aren’t sympathetic to negative visual impacts, but realtors are, since they know the viewshed is an important selling point for a home on the market.

IX. DEP Permitting: Watersheds and Wildlife

Pennsylvania has over 83,000 miles of streams and rivers (second only to Alaska) which drain its over 46,000 square miles. There are regulations, known as Chapter 105, Dam Safety and Waterway Management, that were created to protect the health, safety, welfare and property of the people; and to protect natural resources, water quality and the carrying capacity of watercourses. These regulations are primarily administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA-DEP), however, the Conservation District helps administer parts of this program by providing information and acknowledging some types of permits.

The necessary permits from DEP may be applied for while the wind developer is applying a permit from the municipality. Some wind developers wait to obtain the DEP permit until they’ve obtained municipal approval.

A National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit is required for any point source discharge to waters of the Commonwealth. The Clean Water Program in DEP's regional offices issues the majority of NPDES permits for sewage, industrial waste (IW), IW stormwater, municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4), Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO), biosolids and pesticides activities or facilities that are regulated under the NPDES program. The Bureau of Clean Water (BCW) in DEP's Central Office issues statewide General NPDES permits. If applicants qualify, they may be approved for coverage under a General NPDES permit. The General NPDES Permits that have been issued by BCW are listed below, with links to the Notice of Intent (NOI) forms, instructions and other information.

If a wind project is planned for a watershed that is not ranked High Quality (HQ) or Exceptional Value (EV), a wind developer applies for a general NPDES permit.

If a wind project is planned for a High Quality or Exceptional Value watershed, then the wind developer must apply of an individual NPDES permit since these watersheds receive special protection due to their high water quality. The protection does not allow any degradation of water quality.

It is important to note that EV watersheds may not be degraded – no ifs, ands, or buts.

The classification listings for watersheds starts on page 31 of Chapter 93.

Applications for this permit are posted on the PA Bulletin, which is updated every Friday.

The is the legal notice that a project application has been submitted to DEP and that DEP has deemed the application to be complete. Any citizens who have concerns or comments have 30 days to submit their comments. A public hearing may also be requested within that time period.

Citizens have the right to speak at a public hearing to express their concerns over construction impacts to the affected watershed. Concerns over noise, loss of property value, and aesthetics are not regulated by DEP and are not appropriate topics for comments at a DEP Hearing.

See the Save Broad Mountain website for examples of appropriate comments.

NPDES Individual Permit applications are listed in Section VI:

NPDES Individual Permit Applications for Discharges of Stormwater Associated with Construction Activities.

Northeast Region: Waterways and Wetlands Program Manager, 2 Public Square, Wilkes-Barre, PA 18701-1915.

Carbon County Conservation District, 5664 Interchange Road, Lehighton, PA 18235.

| NPDES Permit No. | Applicant Name & Address | County | Municipality | Receiving Water/Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAD130021 | Broad Mtn Power LLC C/O Algonquin Power 345 Davis Rd Ste 100 Oakville, ON L6J2X1 | Carbon | Nesquehoning Boro Packer Twp | 1A. UNT to Nesquehoning Creek (CWF, MF) 1B. UNT to Nesquehoning Creek (CWF, MF) 2. Nesquehoning Creek (CWF, MF) 3. UNT to Dennison Run (EV, MF) 4. UNT to Dennison Run (EV, MF) |

If you are thoroughly confused by now, or have questions about the DEP permitting process, download this helpful guide:

“NPDES Permits: A Citizen’s Guide to Pennsylvania’s National Pollution Discharge Elimination System Permitting Process.”

This guide was written to help Pennsylvania citizens participate effectively in the NPDES permitting process. It is designed to help you understand the NPDES permitting process, and to give you the tools to help you effectively participate in that process.

DEP’s decision to issue the NPDES permit for a project may be appealed to the Environmental Hearing Board within 30 days of its final decision. The appeal process is thoroughly explained in the Citizen’s Guide.

Appeals:

Notice of Appeal alone does not prevent a permit issued by the DEP from going into effect. In order to enjoin a facility from operating under a newly issued NPDES permit the appellant must file a “supercedeas petition,” pursuant to 35 P.S. § 7514, so called because it requests the EHB to “supersede” the DEP’s permit. The regulations for supercedeas in Pennsylvania are found in 25 Pa. Code §§ 1021.61-64. See more on page 20 of the Guide. Page 21: EHB final decisions may be appealed to the Commonwealth Court, which is a Pennsylvania court of law unlike the EHB which handles administrative adjudications.

The Guide clearly explains the importance of citizen involvement, how to request information using the Right To Know Law, and how to obtain help from environmental organizations, which are listed in the guide.

X. More on Wind Turbines and Wildlife

The Pennsylvania Game Commission (PGC) oversees the birds and mammals in Pennsylvania, while the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC) manages fish, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates. Both of these agencies are involved in the DEP Permitting process, when developers contact the Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory using the PNDI Environmental Review Tool.

DEP has an excellent summary of this portion of the permitting process. See here.

Other state agencies, such as the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) are contacted to determine if any rare plants will be impacted. The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission is also notified, in case any historical resources that will be impacted.

Additionally, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) is consulted if any federally endangered or threatened species may be affected by the wind project. USFWS Biologists in the regional office issue letters outlining what the developers should do if a protected species will be impacted.

The PGC is credited with initiating the Voluntary Cooperative Agreement, in which wind developers pledge to use Best Management Practices to conduct pre-construction and post-construction studies to determine wildlife impacts. Three summary reports of data and a list of wind cooperators is here.

In exchange for following PGC best management practices, the PGC issues, “a special use permit defining the terms and conditions for use throughout the project area by the Cooperator's designated biologist(s) for all bats, birds, and state listed threatened or endangered species which are collected while conducting the Commission’s approved monitoring plan and mortality protocol.”

In other words, wind companies that are voluntary cooperators won’t be held liable or penalized if a protected species is killed.

The PGC decides that State Game Lands are off limits to wind development!

Kudos to the PGC for denying all 19 wind projects proposed for state game lands due to concerns over negative impacts to wildlife and habitats. In 2018, the Board of Commissioners passed a resolution that declared, “as policy that wind energy development on State Game Lands to be inconsistent with the responsibilities of the Pennsylvania Game Commission under both the Game and Wildlife Code and Article I, Section 27 of the Pennsylvania Constitution.” Contact SOAR if you would like a signed copy of the resolution.

This report by FRACTRACKER explains why there is fossil fuel extraction on state game lands, but not industrial wind projects.

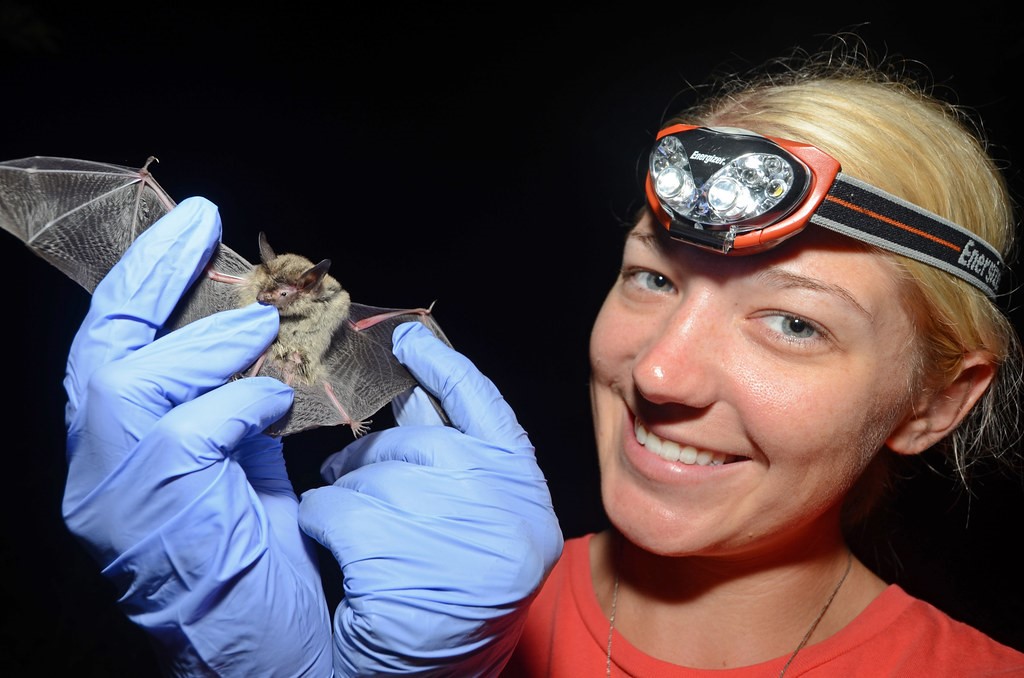

A. Bats:

Unfortunately, since wind turbines are located on the top of forested mountains that serve as migratory pathways for birds and bats, there have been many documented fatalities, and no doubt, many undocumented fatalities. At one point, it was estimated that approximately 25 bats were killed per turbine per year in Pennsylvania. See a more detailed USFWS account here.

If you are wondering why so many bats are killed by wind turbines, read this article that gives a good explanation on the interaction of wind turbines and bats.

On September 26, 2011, during post-construction bird and bat mortality monitoring, an Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis; a federally listed endangered species [USFWS 2011a]) carcass was discovered at the North Allegheny Wind Farm near Turbine A-55. Consequently, a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) was developed and the wind project initiated conservation measures to reduce future kills of this endangered species.

Curtailment Works!

The Casselman Wind Project, built in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, was the first industrial wind project in the United States to study the effects of curtailment on bat mortality. The final report of the two-year study is found here. Based on the results of the study, researchers concluded that, “changing cut-in speeds to the levels we tested offers an effective mitigation strategy for reducing bat fatalities at wind facilities.”

In 2018, the American Wind Wildlife Institute published a white paper “Bats and Wind Energy: Impacts, Mitigation, and Tradeoffs.” Although some progress has been made in curtailment methods and deterrents, these mitigation methods also mean economic losses to the wind industry.

Unfortunately, many wind projects do not follow curtailment procedures and many bats continue to die across the United States. A 2016 report by the Saint Francis Arboreal and Wildlife Association, Inc. details the many shortcomings of the wind industry when it pertains to protecting bats from turbine kills.

Now the wind industry is talking about “smart curtailment.” According to the American Wind Energy Association, it’s the “feasibility of using regional-based weather to predict bat activity and collision risk. Rather than “blanket” curtailment where wind turbines are curtailed at all times bats could be present, they are only curtailed when certain environmental conditions indicate they are at risk of collision.”

Unfortunately, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service does not regulate curtailment unless an endangered bat species is killed. We have speed limits designed to limit accidents and human deaths, why won’t the U. S. government institute curtailment requirements to protect bats?

B. Birds:

While fewer birds than bats are killed in Pennsylvania, many concerns remain regarding turbine impacts to raptors such as Golden Eagles. Although no documented kills of Golden Eagles have occurred in Pennsylvania, it is important to note that post-construction studies of bird mortality are not required. The 15 companies that signed on as PGC Voluntary Cooperators, agreed to conduct a minimum of one year bird mortality surveys post‑construction.

Many proponents point out that wind turbines kill relatively few birds compared to those killed by pollution from fossil fuels, window collisions, cats, vehicles, and poisonings. Yet, the number of birds killed by wind turbines is an additional loss that should not be ignored. Wind turbines are the greatest threat to birds and bats of any green energy source.

In 2012, Dr. Shawn Smallwood published estimates that industrial wind turbines were killing about 600,000 birds a year. In 2013, the first energy company was prosecuted for killing birds: Duke Energy’s wind projects in Wyoming killed 14 Golden Eagles and 149 other protected birds, amounting to $1 million in fines and mitigation.

“This is a welcome action by Dept. of Justice and one that we have long anticipated,” said Dr. George Fenwick, President of American Bird Conservancy (ABC), one of the nation's leading bird conservation groups and a longtime advocate for stronger federal management of the wind industry. “Wind energy is not green if it is killing hundreds of thousands of birds. We are pro-wind and pro-alternative energy, but development needs to be Bird Smart. The unfortunate reality is that the flagrant violations of the law seen in this case are widespread."

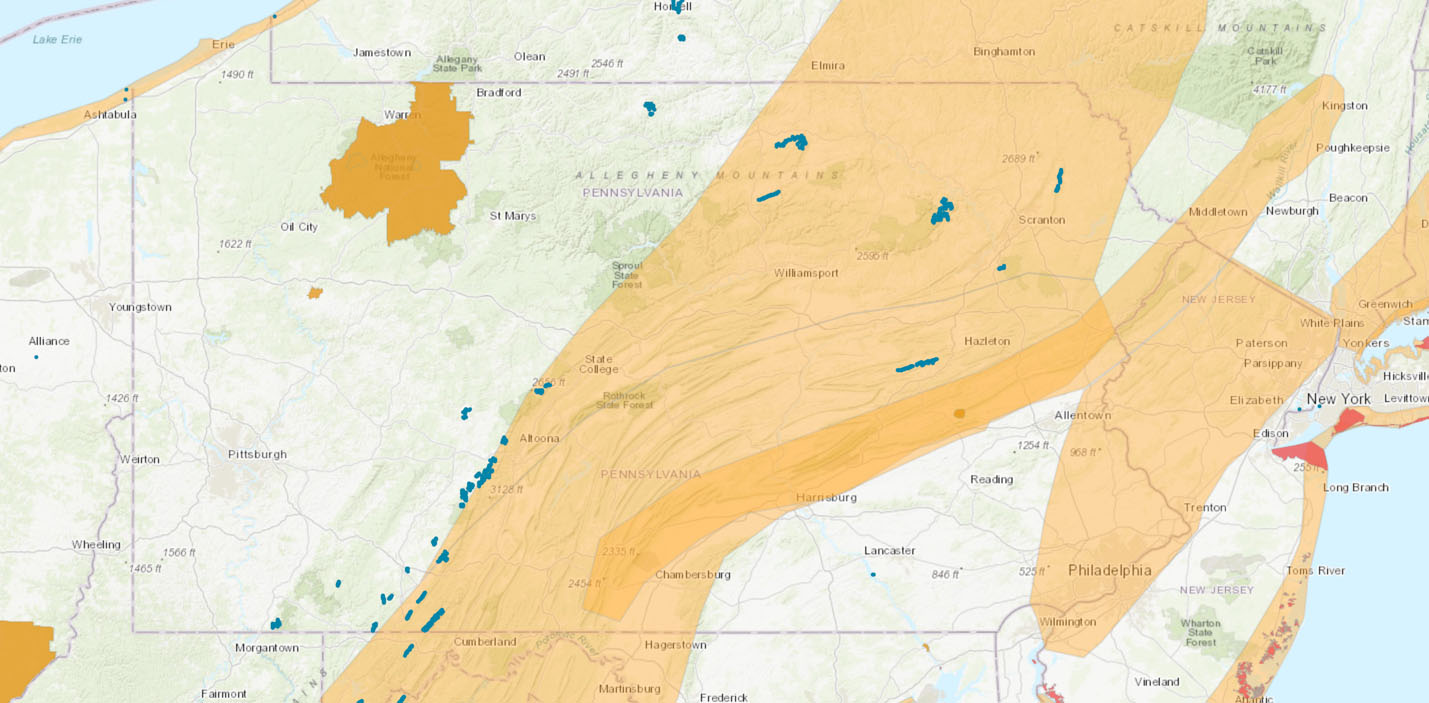

Fortunately, ABC and National Audubon, are advocates of both bird protection and renewable energy – if it is sited correctly. ABC’s Bird Smart program provides resources to help wind developers site projects with fewer bird impacts and it provides a map that details risk areas where there are greater chance of bird collisions at wind projects.

The 3 colors refer to risk areas: red are critical areas, orange areas are of high importance. More details on the risk assessment is found here. The dark dotted clusters are wind turbines. Use the online map to zoom for a closer look, then click on each turbine for specific information about the turbine and the project.

ABC's Map

Clearly shows that many of the existing wind projects in Pennsylvania are located in areas of key migration and key habitat for birds.

When this data is used with the County Natural Heritage Inventories, even more information is available that shows many of Pennsylvania’s forested mountains should be protected from industrial development.

Another very useful web-based mapping tool for Pennsylvania is the Conservation Opportunity Area Tool (COA Tool). This free tool uses data from the 2015-2025 Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan to create web-based maps and reports that anyone can use to see what species and habitat might be impacted by a development project. A report is issued that lists the Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Anyone concerned about Pennsylvania’s conservation of at-risk species will find this tool to be very useful.

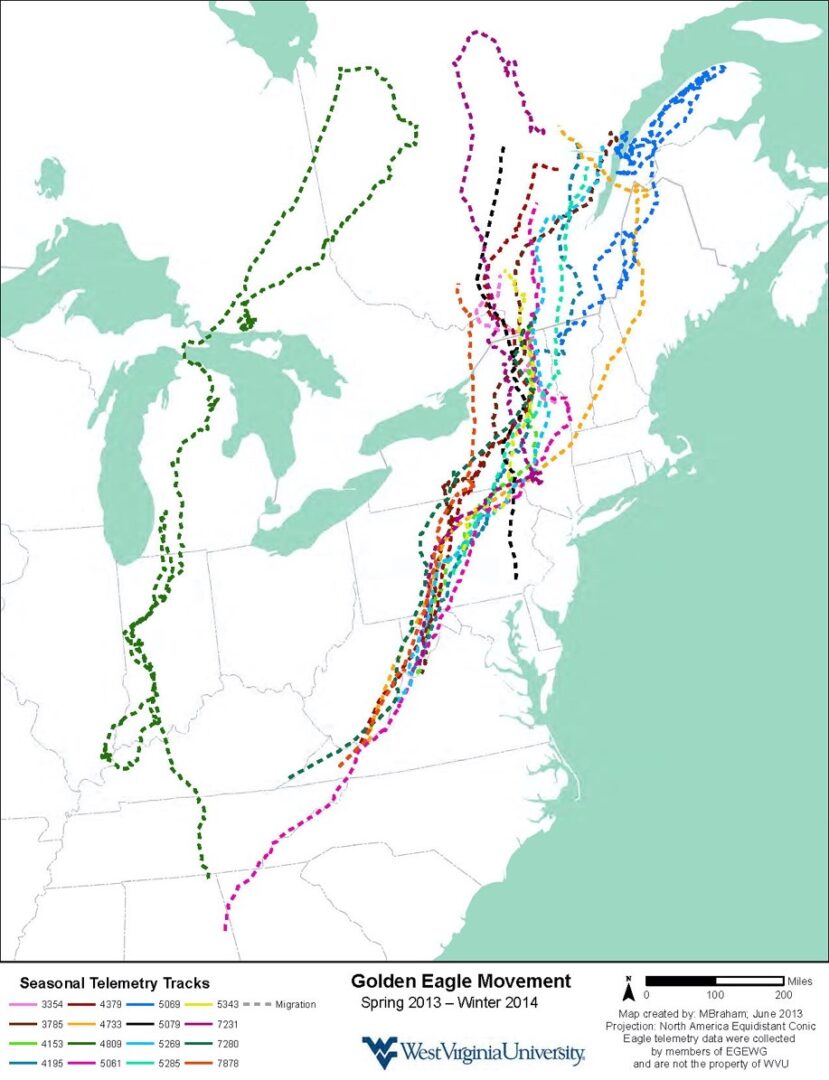

Golden Eagles in Pennsylvania:

Dr. Todd Katzner and Dr. Trish Miller have done extensive studies on Eastern Golden Eagles that winter in the eastern U.S., including Pennsylvania. Back in the early to mid-2000s, Todd and Trish spent many winter days trapping Golden Eagles that migrated over or wintered on Pennsylvania’s ridges in the southcentral part of the state. Dave Bonta writes and shares photos about his family’s experience when they hosted a Golden Eagle trapping event on the top of Bald Eagle Ridge near Tyrone, PA. Dave’s mother, naturalist writer Marcia Bonta, has written at least four articles about the Golden Eagles, including one article in 2010 that featured the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch on Shaffer Mountain – a local name for a small portion of the Allegheny Front in Bedford and Somerset Counties. Shaffer Mountain was slated for an industrial wind project at the time of her visit, so she wrote about concerns that the turbines would kill migrating bats and Golden Eagles:

“These whirling turbines will be 400 feet high and threaten not only the raptors, but also the many migrating bats that use this corridor, bats that are already gravely threatened with extirpation, due to the white nose syndrome which is wiping out whole colonies throughout the eastern United States. The mountain has been designated a Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Area of Exceptional Significance because it has two of the highest-quality trout streams in the East, an endangered Indiana bat colony, and 11,000 acres of forest with only two dirt roads.”

Note: Gamesa’s wind project was terminated in 2012, but the mountain is still at risk since so much of the mountain top is owned by one corporation that most likely would lease again.

Data collected at the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch on Shaffer Mountain, in conjunction the trapping project showed, for the first time, that Golden Eagles breed in northeastern Canada and winter in the Appalachians, including Pennsylvania. These Eagles are known as Eastern Golden Eagles, since they do not interbreed with the western birds.

The mountains in the Ridge and Valley Province are especially important in the spring, since migrating Golden Eagles concentrate in a narrow 30 – 50 mile wide corridor in central Pennsylvania. The population is small – perhaps around 5,000 individuals, so it was recognized that the fate of these birds depended on undeveloped forested mountains for both wintering sites and migratory pathways.

This map from the Katzner Lab shows that Golden Eagles funnel through the western part of the Ridge and Valley Province in Pennsylvania – that’s where the mountains reach their highest elevation. The Allegheny Front Hawk Watch and the Tussey Mountain Spring Hawk Watch record high numbers of Golden Eagles every year. In 2019, hawk watchers also observed the migration on Bald Eagle Ridge near State College, where they could observe eagles and other raptors migrating along the ridge and the valleys.

Unfortunately, the same mountains that attract wind development are the very ones used by Golden Eagles. Fortunately, there are no reported Golden Eagle kills by wind turbines in Pennsylvania at this time, but who is monitoring? Almost all of the wind projects, except the Big Level Wind Project in Potter County, are no longer doing any post‑construction.

Tracking studies showed that Jacks Mountain in Mifflin County, PA is used by Golden Eagles during migration and in the winter, so when Jacks Mountain was under threat by wind developers, Dr. Miller was hired to write a report on Golden Eagles and the potential threats by wind turbines. It is available here.

Drs. Katzner, Miller, and Stoleson summarized their Golden Eagle research in a 214 article, “Quest for Safer Skies,” in which they emphasize that the potential for conflict between energy and eagles is one that “requires careful attention from developers, regulators, managers and researchers of all types.” When one looks at all the wind turbines strung along the Allegheny Front in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, one has to wonder, “Is anyone listening?”

Western Golden Eagles:

Industrial wind turbines continue to kill alarming numbers of western Golden Eagles.

Altamont Pass, CA, where this photo was taken shows a Golden Eagle in comparison to a wind turbine blade. Altamont is the ultimate black hole for Golden Eagles, since so many are killed in that area.

According to Michael Shellenberger (Time Magazine’s Hero of the Environment), “Dr. Smallwood calls the most-studied wind farm in California, Altamont Pass, a population sink for golden eagles as well as burrowing owls.”

While Dr. Smallwood helped improve the siting of wind turbines to modestly reduce their death toll, he also discovered that scientists had been significantly undercounting bird deaths, in part because scavengers like coyotes quickly eat them, and because body parts were outside the search radius.” More of the article can be read here.

Small songbirds and other birds:

Although Bald Eagle and Golden Eagle deaths from wind turbines make the news, more songbirds are killed than raptors. It’s important to note, though, that songbirds reproduce at a faster rate than do raptors. Raptors also use the airspace differently than do songbirds. Raptors do not have the flexibility and maneuverability that songbirds do. Raptors also migrate at lower altitudes than many songbirds. Lights on towers actually attract songbirds because they migrate at night.

Keeping the lights on is most likely a big mistake. During October 2011, over just two nights, almost 500 birds were killed at the Laurel Mountain wind project in West Virginia because security lights were left on at a substation during a foggy night with low visibility. In September that same year, 59 birds and two bats were killed at the West Virginia Mount Storm project under similar circumstances. Earlier, in 2003, at least 33 birds were killed at the Mountaineer wind project. All three incidents were in West Virginia.

The wind industry was quick to point out that the bird kills were due to substation lighting, but the point remains that these kills could have been prevented if proper lighting protocol was followed. Lights out, please!!

C. Forests

Research shows that human-altered habitats put birds at risk and are a major reason why almost 3 billion birds have disappeared from the landscape. Habitat degradation and habitat loss are huge factors pushing many birds and other animals toward extinction. So is climate change.

Should we degrade and destroy wildlife habitats for the sake of mitigating climate change? Some argue yes, SOAR argues no.

Some also argue that wind turbine impacts on wildlife habitats can be mitigated. That may be true in some places, but how does one mitigate all the negative ecological impacts when wind turbines are placed on forested mountains that serve as migratory pathways for birds and bats, habitat for threatened and endangered species, rare plants, and also a source of exceptional value watersheds. There are exceptional watersheds flowing down the slopes of Broad Mountain in Packer Township, Carbon County, PA, but that doesn’t deter wind companies from a proposed project.

Wind turbines on forested mountains don’t just degrade or destroy habitats, these massive projects also degrade the quality of water that often originates on mountain slopes. There is a direct correlation between the amount of forest cover and the quality of water. The more forest in a watershed, the higher water quality. Forests serve as natural sponges, softening and soaking up the rainfall, then filtering and releasing it slowly into springs and streams. Forest cover has been directly linked to drinking water costs – the more forest in a source water watershed, the lower the treatment costs. Those concerns don’t seem to matter to Bethlehem Authority, which leased its watershed to Atlantic Wind for an industrial wind turbine project in Penn Forest Township, Carbon County, PA.

There should be some places that are just off limits to industrial wind turbines. The Nature Conservancy (TNC) thinks so. Even though the area is a prairie and not forested mountains, the Flint Hills in Kansas is such a place. Mitigation just can’t counter the damage that an industrial wind turbine project would do to the tallgrass prairie in the eastern hills of Kansas. That’s why the Nature Conservancy has developed the Site Wind Rite map which uses GIS technology and lots of data sets to inform siting decisions across 17 states in the central U.S.

Let’s hope TNC sets its “sites” on the eastern U.S. next.

Let’s dive deeper into forests.

In Pennsylvania, most of the forests are owned by private landowners. The Center for Private Forests at Penn State works with private forest landowners in the state. According to the Center, there are over 740,000 private landowners who control over 70 percent of Pennsylvania’s forests. Only 9% of forests in the state are State Game Lands and only 12% are State Forests. The Allegheny National Forest is just 3% of the forest land ownership.

There’s a real need for sustainable forest management and the Center provides a lot of resources, training, and support to various groups of private forest landowners. The Center helps landowners understand that forests serve many important ecological functions and that their resiliency is based on species diversity and forest size.

To date, industrial wind projects have only been built on private forest holdings. No wind turbines have been built on state-owned land, although some road crossings have been built on State Game Lands. Many of Pennsylvania’s mountain tops are state-owned land, so that means they are off-limits to wind development.

In 2005, wind development spread rapidly over southcentral Pennsylvania. Wind prospectors knocked on doors, offering lucrative payments to landowners willing to sign a lease. Many landowners didn’t read the fine print, or perhaps didn’t care that they were giving up their property rights when they signed a lease. In some cases, they also gave up their timber rights. Developers were quick to cut trees, bulldoze them under, or set fire to stacks of logs.

Fortunately, many of those wind lease deals fell through, for various reasons, but the higher locations, especially on the Allegheny Front in Somerset and Cambria Counties, sprouted wind turbines.

Forest Fragmentation:

A quick look at today’s projects, listed on the St. Francis Institute for Energy website, shows that Pennsylvania currently has 751 wind turbines (8 were obsolete and removed). Since many of projects were built on forested ridges or plateaus, in long linear formations, there has been extensive forest fragmentation. Some biologists have stated that forest fragmentation might be an even greater threat than estimated bird mortality numbers, since the roads and turbine pads have done extensive damage to the forested habitats.

What is forest fragmentation and why is it a problem?

Michael Snyder does an excellent job of answering this question in an article for Northern Woodlands, Autumn 2014. He explains, “Forest fragmentation is the breaking of large, contiguous, forested areas into smaller pieces of forest; typically these pieces are separated by roads, agriculture, utility corridors, subdivisions, or other human development. It usually occurs incrementally, beginning with cleared patches here and there – think Swiss cheese – within an otherwise unbroken expanse of tree cover.”

He explains that why the effects are so problematic, “By reducing forest health and degrading habitat, fragmentation leads to loss of biodiversity, increases in invasive plants, pests, and pathogens, and reduction in water quality. These wide-ranging effects all stem from two basic problems: fragmentation increases isolation between forest communities and it increases so-called edge effects.”

Many people don’t realize that the effects of forest fragmentation extend 330 feet into the forest; it’s not just the forest opening. Impacts include increased predation, soil dehydration, changes in humidity and light, and invasive species proliferation.

It's true that forest fragmentation may benefit animals like deer, wild turkey, and even timber rattlesnakes by allowing more sunlight to reach the forest floor and provide more food or cover. Wind companies often say that a wind project helps wildlife, but they are usually ignoring all the species that don’t benefit. The state threatened Allegheny Woodrat is a good example of a species that’s already in trouble and in even more peril due to forest fragmentation from wind projects.

One of the top conservation organizations in the state, collaborated with The Nature Conservancy and Audubon Pennsylvania to develop a Pennsylvania Energy Impacts Assessment in 2010. Although dated, but still relevant today, this study modeled the potential impacts of Marcellus Shale natural gas and wind development in Pennsylvania. These groups understood that not only was the forest removed for energy extraction, but that forest fragmentation reduced the quality and viability of Pennsylvania’s forests.

Sadly, many of the potential impacts described in this report have come true as even more well pads, pipelines, and wind turbine projects intrude on the wild lands and wildlife of Pennsylvania. When the report was published, there were 319 wind turbines in 12 wind projects, mainly on the Allegheny Front and in northeastern PA. The number of turbines has more than doubled to 751 wind turbines. Researchers digitized the amount of impact per turbine and found it to be a total of 15.3 acres of direct and indirect impacts.

Although calculations showed that projected forest losses and affected forest interior habitats would not be significant, they did conclude that impacts could be significant for individual large forest patches where wind development takes place.

Key Findings of this study did not project a high degree of impact on forest habitats or forest interior bird habitats, but as wind turbines become larger the amount of impact may increase significantly.

Conclusion: